10/43

10/43

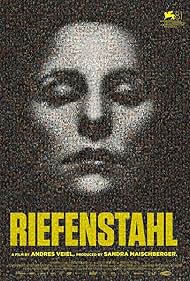

Explores the artistic legacy of Leni Riefenstahl and her complex ties to the Nazi regime, juxtaposing self-portraiture with evidence suggesting awareness of the regime’s atrocities. Can derogatory propaganda also be great art? It is a question that will always arise when discussing the work of German director Leni Riefenstahl. She is admired as one of the greatest German directors of all time (by Quentin Tarantino, for example), but she is also despised for making the Third Reich look glamorous. Riefenstahl herself always denied being a Nazi. In her view, she was an artist working for Hitler. In interviews she has always insisted that she was unaware of the regime’s atrocities. After her death in 2003, this image of herself was quickly shattered. The striking contrast between her own statements and historical facts was already the subject of the recent television documentary “Riefenstahl – The End of a Myth” and is explored further in the documentary “Riefenstahl”. 39;.Director Andrés Veiel carefully combed through her entire estate, searching for letters, newspaper clippings and official documents in order to confront Riefenstahl’s words with reality. This research shows even more clearly how manipulative Riefenstahl was. But at the same time, it is fascinating to see how her enormous ego and fearless ambition helped shape her place in film history. In a Q&A session during the Ghent Film Festival, Veiel said that he initially wanted to create an avatar of Riefenstahl in his film – an alternative Leni, created from personal letters and diary fragments from her estate. But in the end the material itself was so clear that it could speak for itself. There is no doubt that Riefenstahl had a deep sympathy and admiration for the Nazi movement. Veiel convincingly shows that her own worldview was completely in line with Nazi ideology. The film contains a treasure trove of historical material. Very revealing are the images of the television interviews, taken when the cameras remained on while the interview was interrupted. Riefenstahl becomes very angry when questioned about her responsibility as an artist and her involvement in the Nazi movement. But even more revealing are the recorded telephone conversations Riefenstahl had with her numerous admirers. Every time her artistic integrity was questioned, she received letters of support and sympathetic phone calls. Many Germans agreed that in the 1930s it was very difficult to resist the Nazi movement and that passive supporters of Hitler were judged too harshly. Andres Veiel himself considers his film a lesson for today. Riefenstahl's ability to recreate her own image and shape the past in her favor is similar to the plethora of fake news created by populists like Donald Trump.